As our system continues to grow, we have distributed it across multiple servers, multiple databases, and even multiple data centers.

But as soon as you distribute your data, one thing becomes clear:

You can't have everything – you have to choose what you want to sacrifice.

This trade-off is captured beautifully in one of the core principles of distributed systems:

The CAP Theorem

What Is the CAP Theorem?

The CAP Theorem (also known as Brewer's Theorem) states that in a distributed data system, you can only guarantee maximum two out of the following three properties at the same time:

| Letter | Property | Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| C | Consistency | Every node sees the same data at the same time. In other words, all nodes see the same data at the same time. |

| A | Availability | Every request gets a response (even if some nodes fail), without guarantee that it contains the most recent write. |

| P | Partition Tolerance | The system continues to work even if network communication breaks between nodes. |

A distributed system must handle partitions (network failures are inevitable).

So in practice, you usually chose between Consistency and Availability when partitions occur, as Partition Tolerance is mandatory.

The Three Types of Systems (CA, CP, AP)

| Type | What It Prioritizes | What It Sacrifices | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| CA (Consistency + Availability) | Consistent and available as long as there’s no partition | Fails under network partition | Traditional single-node RDBMS (MySQL before sharding) |

| CP (Consistency + Partition Tolerance) | Always consistent, even during partition | May become temporarily unavailable | HBase, MongoDB (with strict consistency), Google Spanner |

| AP (Availability + Partition Tolerance) | Always available, even if data might be inconsistent temporarily | Eventual consistency | Cassandra, DynamoDB, CouchDB |

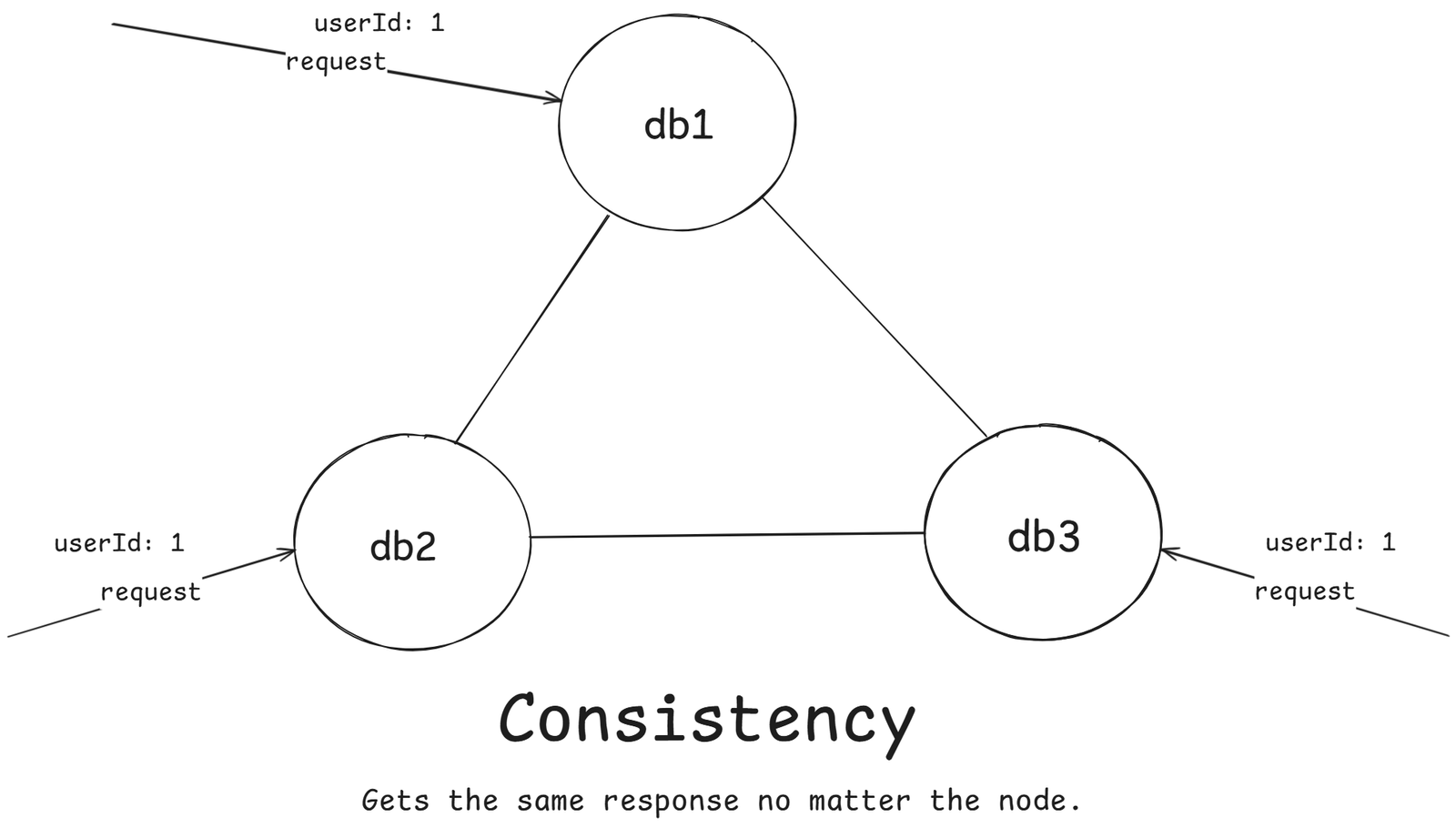

Consistency

Every read receives the most recent write.

If you update data on one node, all other nodes must immediately reflect that update before any other client read it.

As shown in the figure above, user request for the userId: 1 to all the nodes, In case of consistency, the response should be same.

If there is any update in any of the node then all the other nodes should also get updated. Thus we can say, client gets the same data at the same time no matter the node.

Let's take the case of Instagram, where user changed the profile picture in the db1, then if anyone hit the request to watch your profile in the db2, and db3, then they should see your updated profile picture.

Example:

Banking systems – When you transfer money, you can't afford inconsistent balances – it must be strongly consistent.

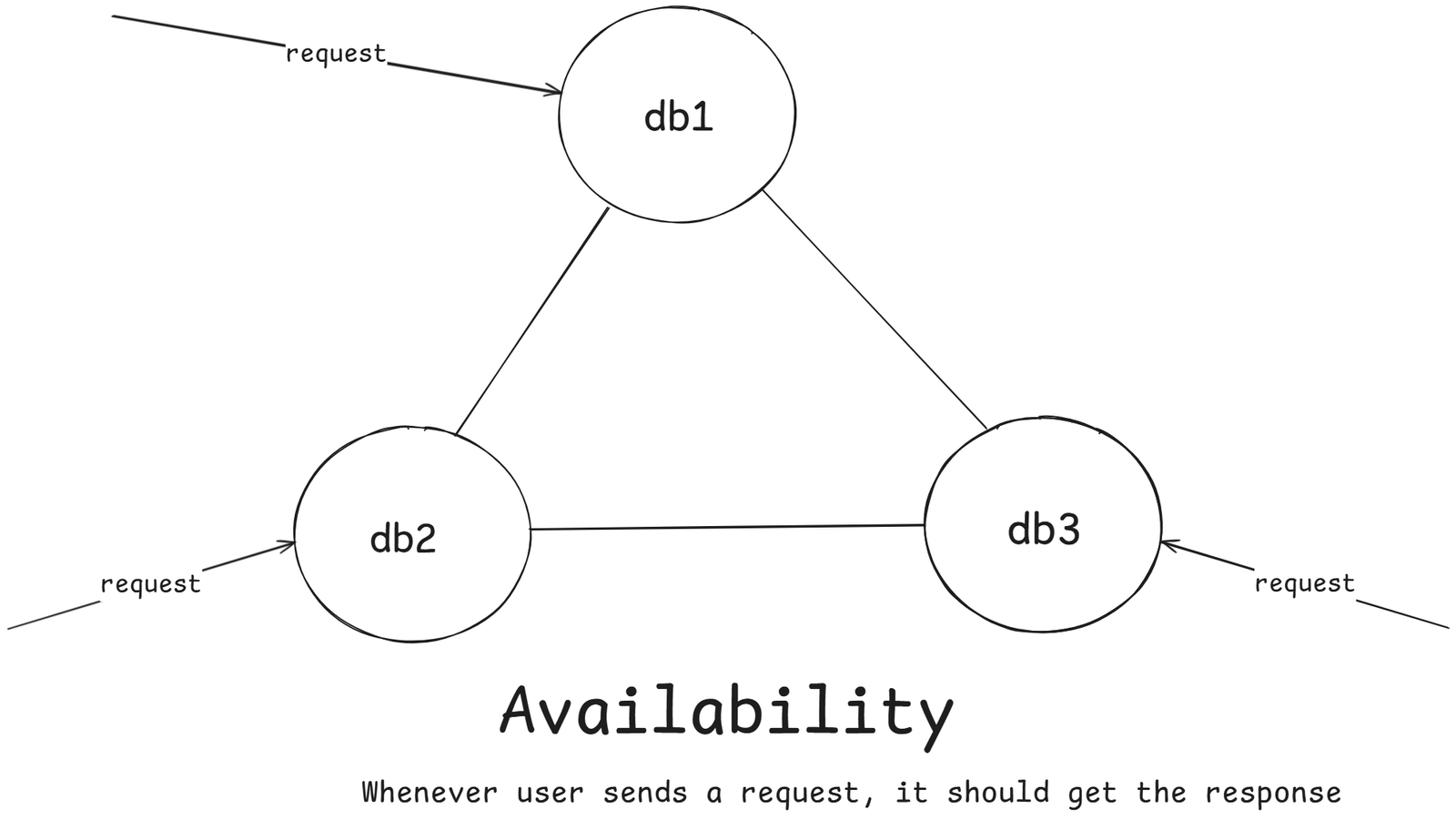

Availability

Every request receives a (non-error) response, even if some nodes are down.

The system will never refuse to respond, even if some data might be slightly outdated.

Example: Amazon product pages

If one database node fails, other still serve cached data – better to show slightly old info than to be unavailable.

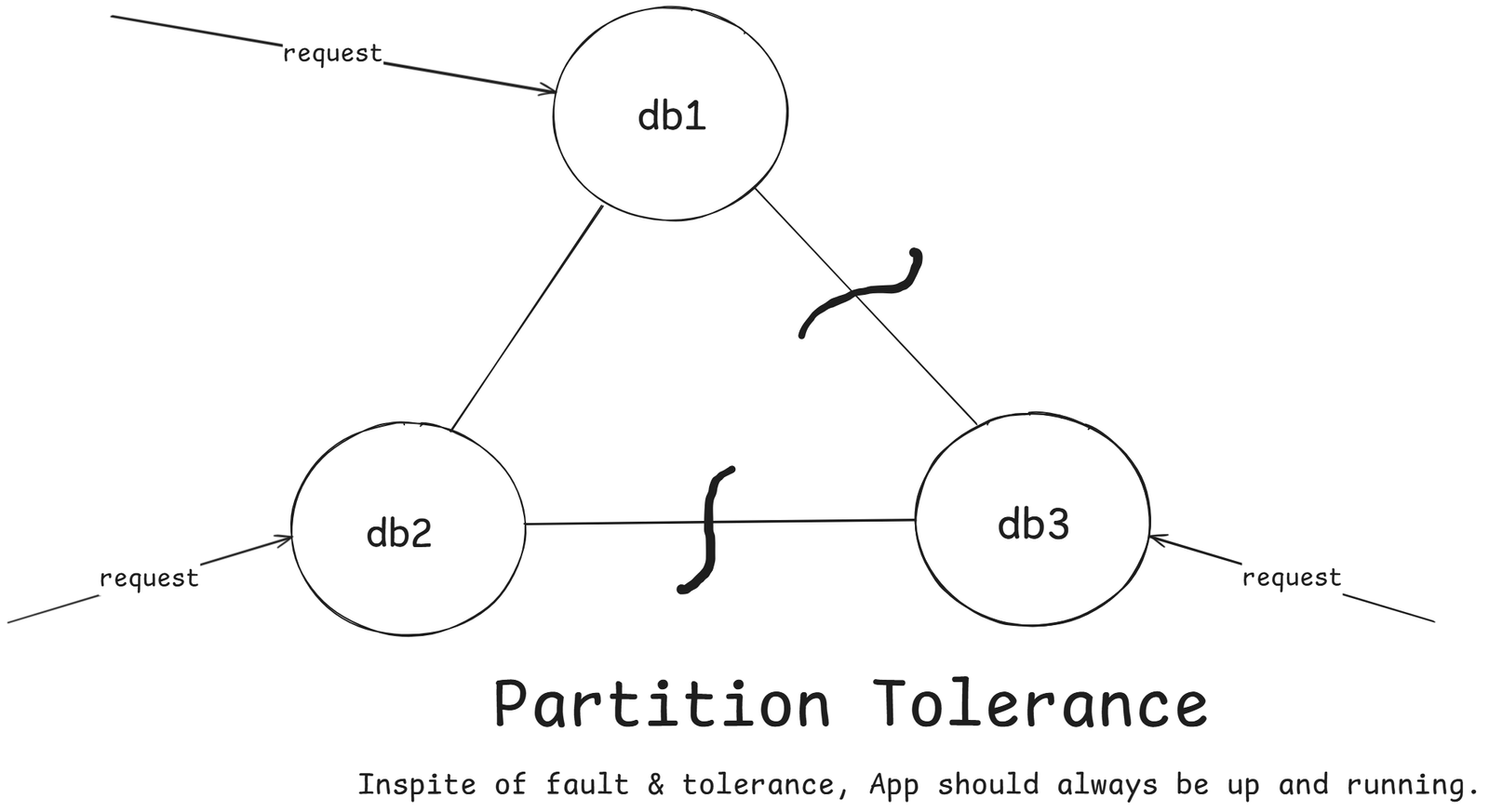

Partition Tolerance

The system continues to operate even when some nodes cannot communicate with each other.

In distributed systems spanning multiple data centers or regions, network partitions are inevitable – links can drop, timeouts happen, and packets get lost.

Partition tolerance means the system can recover gracefully from such failures.

A partition occurs when:

- Network links fail

- Nodes crash temporarily

- Data centers lose connectivity

In other words, part of your distributed system is isolated from the rest.

Example:

If your US and EU databases lose connection, both should keep running (with some compromise).

The Real Trade-off: You Must Choose

When a network partition happen (P), the system must decide:

- Should it stop serving requests until everything syncs?

(Consistency) - Or serve data from available nodes even if it's outdated?

(Availability)

That's the CAP dilemma.

Consider the picture given above as an distributed nodes architecture.

Suppose connection between db3, db2 and db3, db1 broke then it means db3 is running but not able to communicate with db1 and db2.

And out application supports Partition Tolerance.

Now we need to prove that we can't achieve both Consistency and Availability.

Data to be Consistent:

When a user updated the profile picture on db1 and another user trying to get that profile on db3. This way the second user will get stale data as profile picture is only updated on db1 and replicated to db2 also but not to db3 (break in connection).

To Make it consistent:

We need to prevent the write operation on db1 and db2 node until the broken link to db3 is restored.

Now if any user try to update the profile picture on node db1 and db2 then we denied this action. However because of this Availability is compromised.

Availability means everyone should get response but we didn't give the status OK (HTTP = 200).

To Make it Available:

We have to allow all operations but doing so our system will not be consistent. As if some user updated the profile pic on db1 and it will be reflected to db2 also but not on db3. So anyone accessing that profile from db3 will get stale data.

So we compromised the consistency.

Consistency vs Availability

Consistency:

All users see the same data at the same time.

What it means:

- Every read returns the most recent write.

- The system behaves like a single, up-to-date database.

- No stale data.

When it's preferred:

- Financial systems (bank balances, trades)

- Inventory systems that must avoid overselling

- Anything where wrong is worse than slow

Trade-off

- May require waiting for nodes to synchronize

- Can reject requests if all replicas aren't aligned

- Strong consistency -> lower availability

Availability

The system always responds, even if it might return older data.

What it means:

- Every request gets some response, even during failures.

- System prioritizes uptime and responsiveness.

- Might return stale data if nodes cannot sync.

When it's preferred:

- Social media feeds

- Caches and content delivery

- Services where slightly outdated is acceptable.

Trade-off:

- More uptime -> weaker consistency guarantees

- Clients might temporarily see different data

Availability Numbers

In system design, availability is the percentage of time a system is operational and serving requests over a given period (usually a year).

It is usually expressed in nines, like “99.9% availability” or “five nines.”

Calculating Availability

Formula:

Availability (%) = Uptime / (Uptim + Downtime) * 100- Uptime = Time system is operational

- Downtime = Time system is unavailable

Common Availability Levels

| Availability | Downtime per year | Downtime per month | Downtime per day | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 99% (2 nines) | ~3.65 days | ~7.3 hours | ~14.4 min | Basic level, often acceptable for internal apps |

| 99.9% (3 nines) | ~8.76 hours | ~43.2 min | ~1.44 min | Standard SLA for many SaaS applications |

| 99.99% (4 nines) | ~52.6 min | ~4.32 min | ~8.6 sec | High availability systems; e-commerce, banking |

| 99.999% (5 nines) | ~5.26 min | ~25.9 sec | ~0.86 sec | Mission-critical, extremely resilient systems |

| 99.9999% (6 nines) | ~31.5 sec | ~2.59 sec | ~0.086 sec | Ultra-critical systems like flight control, stock exchanges |

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *