The Historical Evolution of API Gateways

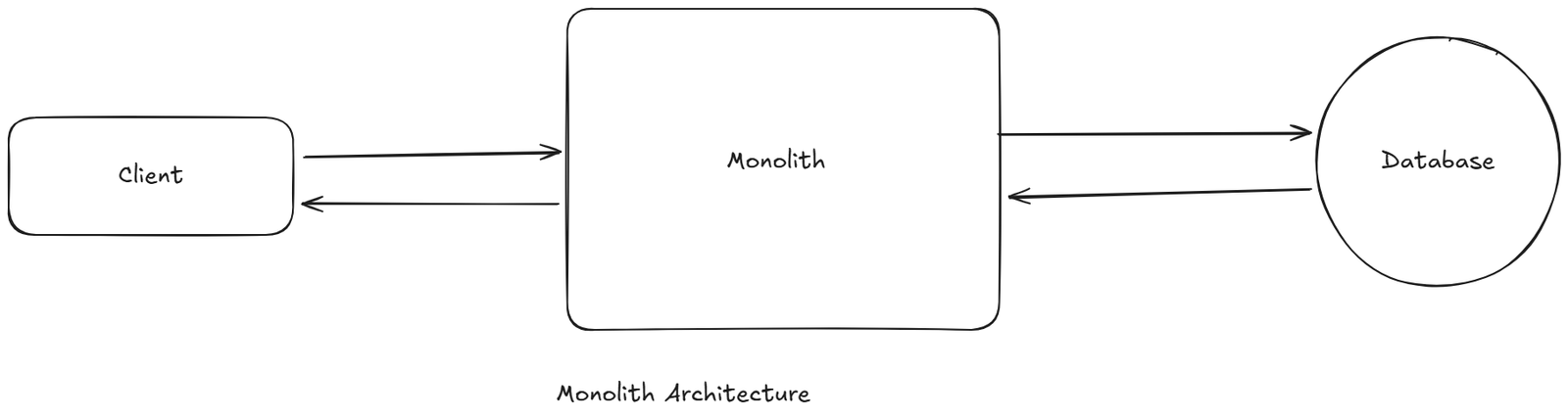

The Monolith Era (Pre-2005)

A monolithic application was a single, tightly coupled software system where:

- UI

- Business logic

- Data access

- Security

- Integrations

… all lived inside one codebase, deployed as one unit, and scaled as one process.

Typical characteristics:

- One WAR file (Java)

- One EXE (Windows)

- One deployment artifact

- One database

- One operations team

There was no concept of independently deployable services.

If you changed one line of code:

The entire system had to be rebuilt and redeployed.

The monolith itself was the gateway:

- It handled authentication

- It handled routing (internally via function calls)

- It handled validation

- It handled business logic

- It handled database access

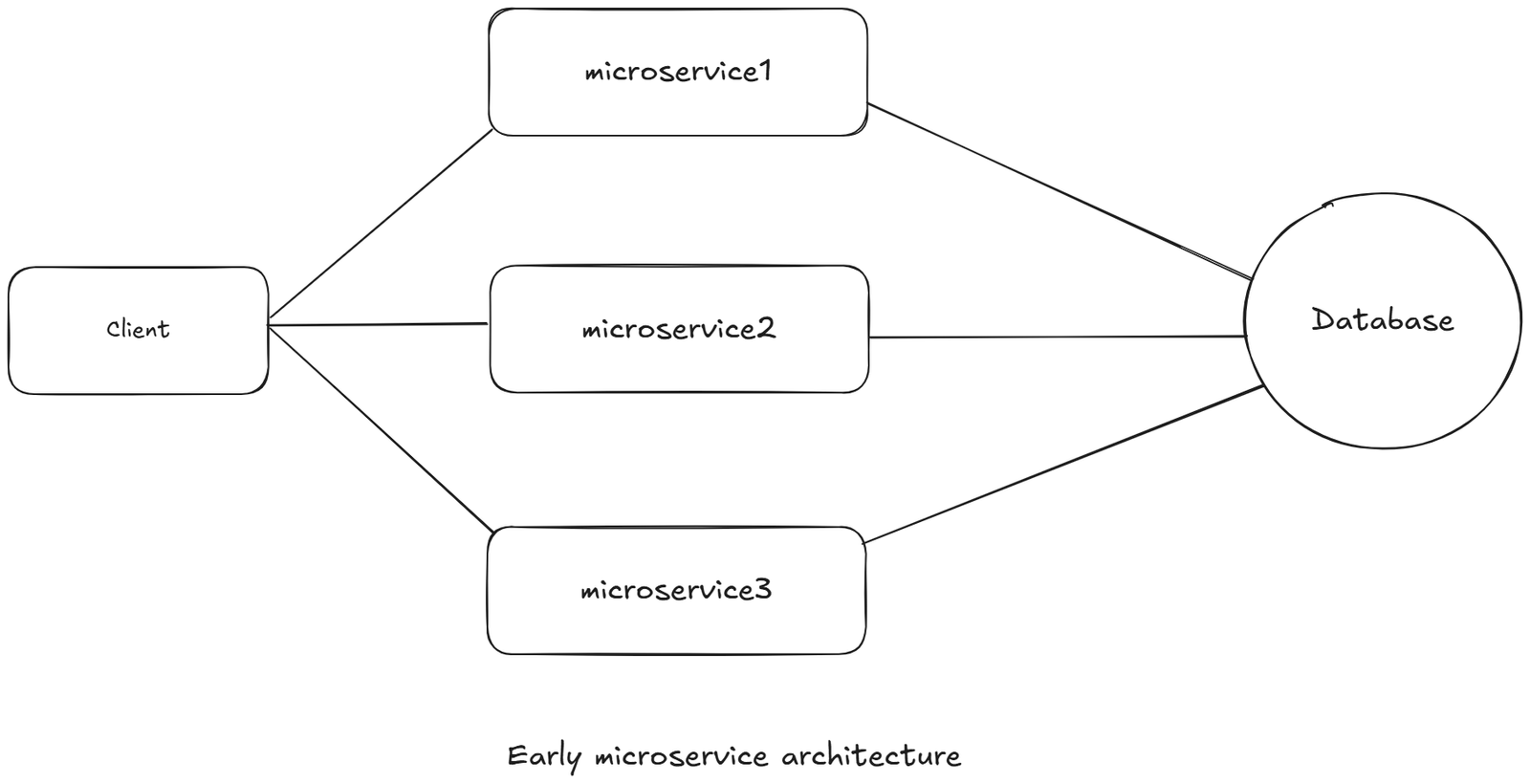

Microservices (Around 2010)

The original definition of microservices was not about buzzwords. It meant:

- Small, independently deployable services

- Each service:

- Owned its own logic

- Often owned its own database

- Had an independent lifecycle

- Services communicated over:

- HTTP/REST

- Message queues

In the monolith era:

Client -> One ApplicationIn microservices:

Client -> ??? -> 30 services -> 60 services -> 100 servicesWithout an API Gateway, early microservices systems made clients directly call:

- Auth Service

- User Service

- Order Service

- Payment Service

- Inventory Service

- Notification Service

This caused immediate disasters:

- Clients had to understand internal service topology

- Client had to know the URL of every single microservices and when to call each of them respectively.

- If there is an master services like microservice1, which would redirect the request to other services accordingly.

- Every client implemented its own retry logic

- Auth logic duplicated everywhere

- No central rate limiting

- Security was inconsistent

- Network latency exploded

Birth of API Gateway (2014)

Netflix is widely credited with formalizing the API Gateway pattern.

By 2010:

- Backends had:

- 50-200+ microservices

- Independent deployments

- Independent failures

- Clients had:

- Web apps

- Mobile apps

- Partner systems

- Public developers

But there was no single entry point anymore.

Clients were directly calling:

- User Service

- Payment Service

- Order Service

- Inventory Service

This caused:

- Tight coupling between clients and internal services

- Zero centralized security

- Zero rate limiting

- Zero API version governance

- Extreme latency explosion

- Massive security exposure

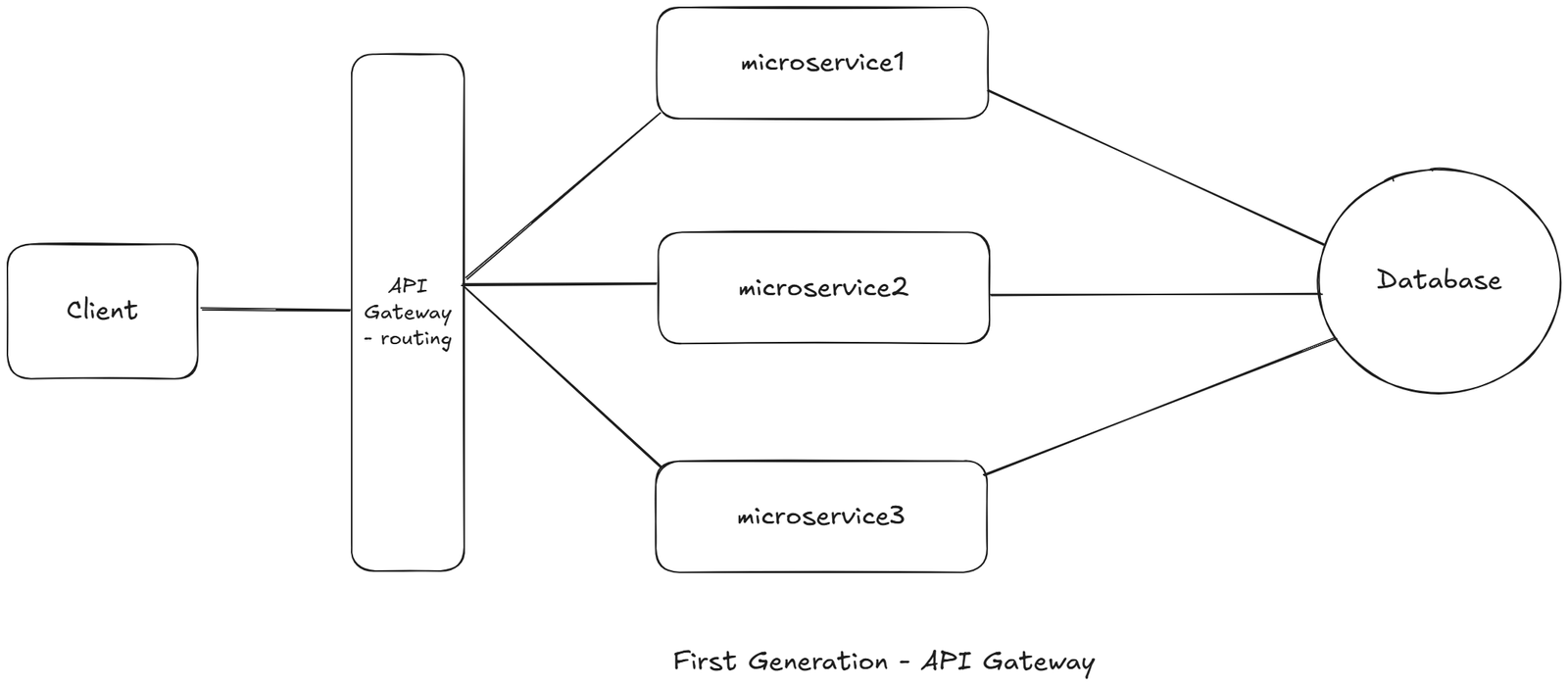

This chaos forced the creation of the First-Gen API Gateway.

It focused on three core capabilities only:

- Routing

- Authentication

- Aggregation

They were not yet full API platforms.

This solved the routing problem.

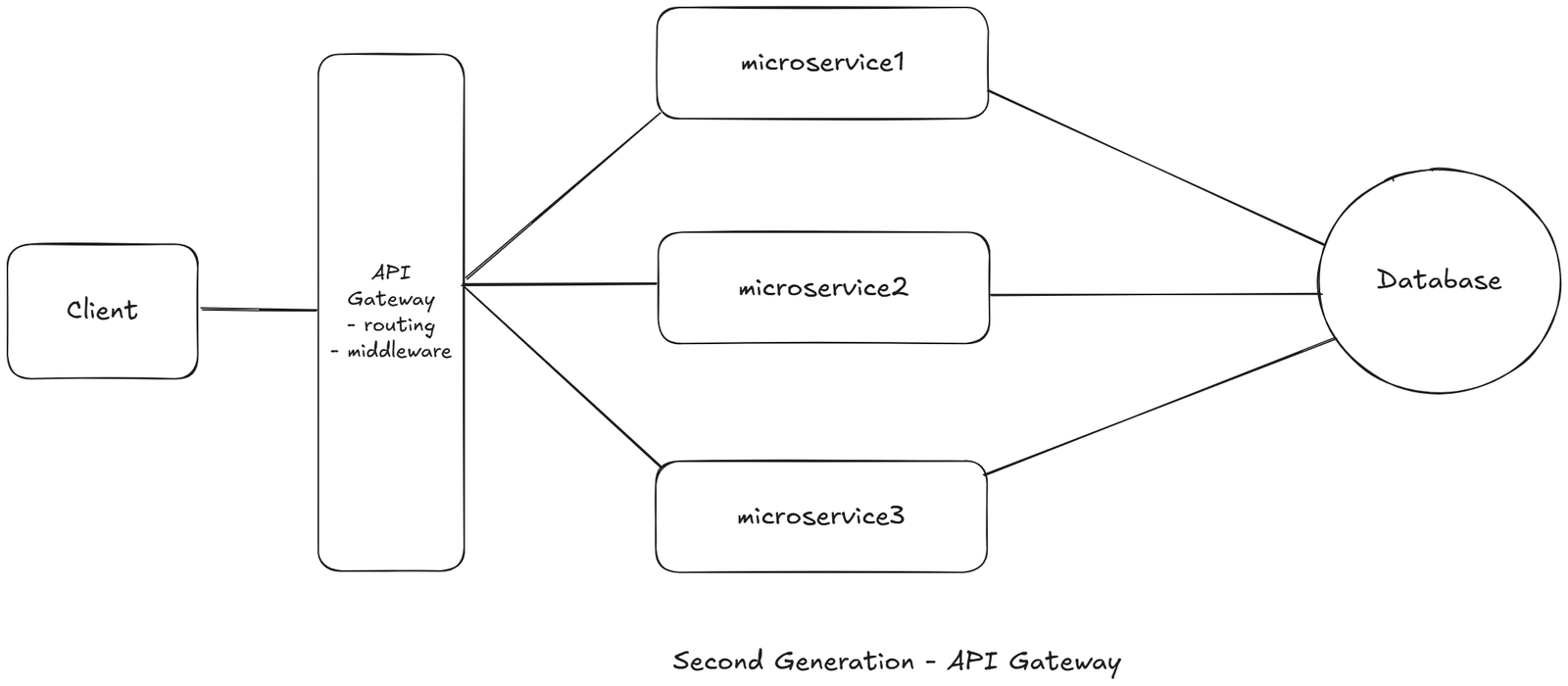

Second Generation API Gateway

Every microservice now contained the same boilerplate code:

- Authentication

- Authorization

- Rate limiting

- Logging

- Metrics

- CORS

- Request validation

- Header propagation

- Retries and timeouts

- Circuit breaking

This duplicated logic created operational entropy.

Imagine you now have 50 microservices

- User Service

- Order Service

- Payment Service

- Inventory Service

- Notification Service

- …

Now think about this question:

Does every one of these services need to do security, logging, rate limiting, validation, etc.?

Sadly, in early microservices YES – they all did it themselves

So every service had this repeated code:

- JWT token validation

- Role checks (admin/user)

- Logging requests

- Sending metrics

- Checking bad input

- Handling retries

This means:

- Same code written 50 times

- Security bugs 50 times

- Config updates 50 deployments

This is what we call repeatable / cross-cutting code.

Because Earlier API Gateway (only did) this:

- Route request -> correct service

That's it.

But Next-Gen API Gateway became a “heavy middleware layer” that said:

“All common logic will run ONCE at the gateway – not inside every service”

So the API Gateway started doing this for ALL services:

- Authentication

- Authorization

- Rate limiting

- Request validation

- Logging

- Metrics

- Header handling

- CORS

- Throttling

- Basic retires

Now microservices only do:

- Business logic

- Database work

- Domain rules

Nothing else.

What is an API Gateway?

An API Gateway serves as a single entry point for all client requests, managing and routing them to appropriate backend services.

A programmable reverse proxy that sits between clients and backend services and centralizes all cross-cutting concerns.

In simple words:

It is the single front door of your entire backend system.

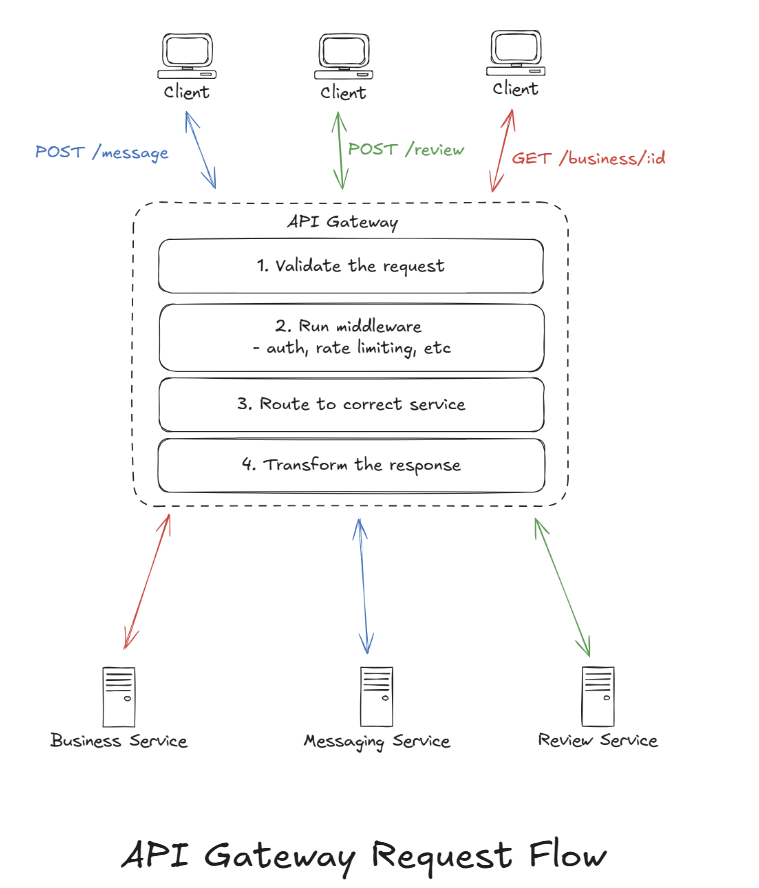

API Gateway Process

When a request enters an API Gateway, it passed through a well-defined pipeline. Each stage has a specific responsibility, and together they protect your backend, enforce policy, and ensure only high-quality traffic reaches your services.

1 Request Validation (First Line of Defense)

Before doing anything else, the API Gateway verifies that the incoming request is structurally correct and complete.

This includes:

- Checking if the URL/path is valid

- Verifying that mandatory headers are present (e.g, Authorization, API key)

- Ensuring the request body matches the expected schema (JSON/XML format)

- Validating request size limits

- Checking content-type correctness

Why this matters:

Early validation prevents garbage traffic from reaching the backend.

For example:

- A mobile apps sends malformed JSON

- A client forgets to include an API key

- A bot sends a 50MB payload to a 5KB endpoint

There is no business value in forwarding these requests. The gateway immediately rejects them with a clear 4xx errror and saves:

- Compute

- Network cost

- Backend thread pools

- Database load

This step alone significantly improves overall system stability.

2 Middleware Layer (Cross-Cutting Infrastructure Logic)

After validation, the request passed through the middleware pipeline. This is where all cross-cutting, reusable logic is applied.

Typical middleware responsibilities include:

- Authentication (JWT, OAuth, API keys)

- Rate limiting & throttling

- IP whitelisting/blacklisting

- SSL/TLS termination

- CORS handling

- Request and response logging

- Request compression

- Timeout handling

- API versioning

- Request size enforcement

- Traffic shaping

3 Routing (Where Does This Request Go?0

Once the request is authenticated and allowed, the gateway needs to decide which backend service should handle it.

Routing decisions are based on:

- URL path (

/users/* - HTTP method (

GET,POST) - Request headers

- Query parameters

- API version (

/v1,/v2)

A conceptual routing table looks like this:

routes:

- path: /users/*

service: user-service

port: 8080

- path: /orders/*

service: order-service

port: 8081

- path: /payments/*

service: payment-service

port: 8082The gateway performs a fast lookup in its routing table and forwards the request to the correct backend service.

Clients never need to know:

- Where services are deployed

- How many instances exist

- What ports they run on

That complexity is fully abstracted by the gateway.

4 Backend Communication & Protocol Translation

Once routing is resolved, the API Gateway forwards the request to the target service.

Most commonly:

Client -> HTTP/JSON

Gateway -> HTTP/JSON -> BackendBut sometimes:

Client -> HTTP/JSON

Gateway -> gRPC -> BackendIn such cases, the gateway performs protocol translation. It converts:

- REST to gRPC

- JSON to Protobug

- External API formats into internal service formats

This is powerful because:

- Clients get a simple, universal API

- Backend teams are free to choose the most efficient internal protocol.

This pattern is especially common in:

- High-performance systems

- Internal microservice communication

- Streaming-based architectures.

5 Response Transformation (Client-Friendly Output)

Once the backend responds, the API Gateway may transform the response before returning it to the client.

This can include:

- Formatting changes (gRPC -> JSON)

- Removing internal-only fields

- Renaming response attributes

- Aggregating multiple service responses

- Applying compression (gzip, brotli)

- Enforcing consistent API shape

Example conceptually:

- Client requests user profile over HTTP

- Gateway converts request to internal gRPC call

- Backend returns Protobuf

- Gateway converts result back to JSON and sends it to the client

This allows:

- Clean external APIs

- Flexible internal service evolution

- Backward compatibility

6 Caching (Performance Accelerator)

Before returning the response, the gateway may cache it if the data is non-user-specific and frequently accessed.

Common caching strategies:

- Full response caching (entire API response)

- Partial caching (specific response fields)

- TTL-based expiration

- Event-driven invalidation

Cache storage can be:

- In-memory (for ultra-fast response)

- Distributed cache like Redis

- CDN-backed edge caching

Caching is ideal for:

- Public catalogs

- Product lists

- Configuration data

- Static metadata

- Feature flags

Bad candidates for caching:

- User-specific data

- Financial transactions

- Real-time state

Used correctly, caching:

- Reduces backend load

- Improves latency

- Lowers infrastructure cost

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *